I was asked an interesting question from one of my ARC readers about what inspired me to write this book.

The answer is… complicated. A lot of the story was made with some bits and pieces of my own personal life, but it comes from a place of being the “smart kid”.

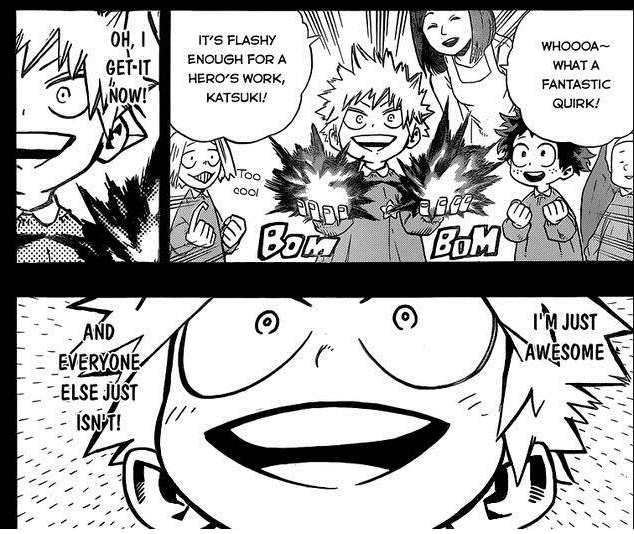

Let me explain; for some readers, or some people who watch the blog… I’m going to post a panel from a manga. A pretty character defining scene; for context, the characters in this universe are all given “quirks”, which are essentially superpowers. Some are born with abilities while others aren’t.

While I was not raised to believe that I was better than anyone else (in some regards; I was encouraged to not be discouraged by anyone), growing up, I had this notion that I was smart. Generally, the only problem I’d have in class was my ability to sit and pay attention. And math. Math was annoying. But once I got it, I felt like I just knew it. I wasn’t an all “A” student by a wide margin, but I had this idea that things would come easy to me. If it came easy to me, then I didn’t need to try.

In elementary school, because one of the teachers stopped checking homewor, I stopped doing math homework. I understood it well enough and it was easy to me, so why bother trying? Writing assignments were a breeze for me, and I’d always get As in ELA and Social Studies, so again, if I knew it, why try?

I got As in English. Cs or Bs in math. The rest of the classes didn’t matter because I got As there too. The threshold for success was in my control, and everything was great!

Until college.

I’m more than sure that there’s a lot of people that have been shell-shocked by the workload and work-difficulty that college brings. I was envious of the people that were able to just… adapt to the change without much trouble because, to me, it meant they were somehow more ‘functional’ than I was. As someone who had undiagnosed ADD and practically coasted through school with good grades, I felt like I was one step away from being the kind of person that lives with their parents at 40 or 50.

This gets into another facet of this whole thing; being raised as a black man, I was made very aware of my standing in society. What my white peers could do, I couldn’t. My successes had to be double, or triple of that of my white peers. On top of being reminded to pay attention and focus, I felt like I was under constant pressure to succeed which– yes, I was; I’m not entirely sure how any parent wouldn’t want their kid to achieve their goals, but my own mind exasterbated the expectations to a monumental amount. Anything that made me feel like I failed or didn’t meet the expectations was devestating to me for a while. It was bad because any impression that I had of failing made me feel I’d be in a box somewhere. It made me really combative with my family when I saw my friends able to be free of their responsibilities and just… do whatever they wanted without care. I was envious, absolutely, and they wanted to pull me out of an ‘abusive family’, when in reality, I was putting myself under stress.

Meeting the expectations of my family was definitely something I wanted to do, but I wanted to be free to do the things I wanted to do without fearing it would affect my future.

That’s why Kane is so antsy about making decisions. With every decision made, there’s a consequence. Fear of consequence is what leads to inaction. And that fear can keep growth from happening.

Now, I’m not saying that for people to jump on the chance to do something drastic, but I do want to be clear in that calculated risks can lead to pleasure or pain. If it’s the former, then great! It’s fine to keep doing it as long as it doesn’t hurt anyone. If it’s the latter, then it may affect you, or other people around you. The first thing that needs to be done when faced with a failure that affects those around you is to forgive yourself. Being unable to do that will always lead to being at odds with everything you do. You’ll hate yourself for not meeting the expectations of others when, really, it should be your own expectations. And then, regardless of the consequence, you make strives to do better. You don’t say that you’ll do better, you just do better. Maybe you’ll make the same hiccup again, or you’ll notice when you’re about to make the same mistake as before. That’s okay. Er, depending on whatever it is you’re doing. The point is, we grow from facing our mistakes and vowing to do better. It’s easier said than done, and a lot of it involves being mindful of your own reactions to things. That said, mistakes can be big enough to turn someone’s life upside-down, or mistakes can be small and only change the course of life an inch.

We are not defined by our errors, but what we do after. It took a long time for that lesson to stick with me, and it’s what inspired me to write this series as a whole; to explore the ends of consequences and forgiveness.

Leave a comment